(Scheme (is (quite (crazy))))

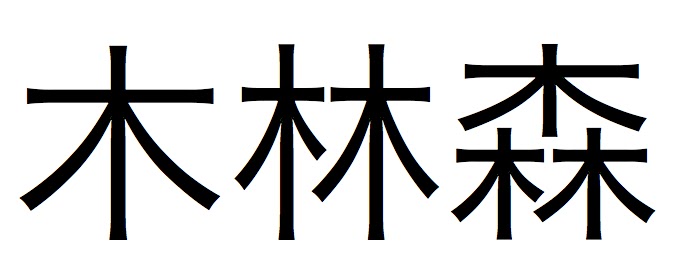

A written language is defined (roughly) by some marks, and some meaning behind those marks. In roman alphabet we assign sounds to each character, when we unite letters in specific orders we get a particular sound that is associated (hopefully) with a concept. But not all writing works like that, japanese Kanji associates the characters with concepts, not sounds, so here we have the characters for tree, woods, and forest. Is just the repetition of the concept of tree:

Interesting right?

Well, why my gibberish? Because for someone who has only been exposed to Javascript, a bit of Python, and even less C, Scheme surely looks completely different, not only syntactically, but in the way the language is structured and how parts work with each other. Today I started reading “The Little Schemer”, and these are the things I learned by experimenting with the very first chapter.

First thing it caught my attention was that everything is prefixed, even addition. The structure being (operator operand1 operand2…) so even a basic 2 + 2, with infix notation, would be (+ 2 2) in Scheme. Actually I regard that very good, since it makes you wrap your head around that +, - ,* are functions, so it makes sense to write the function and then the arguments, like doing sum(2, 2) in Javascript (provided you define sum). Also, no comma to separate values, empty space will do the trick.

Building Blocks

Is different to provide definitions, partially because the book makes a conscious effort by teaching you by examples and makes YOU extract your own definition, I feel like I’m a machine learning model that gets fed data, only less efficient.

(this is a (S-expression))

In the code above this, is, and a are both S-expressions and atoms. (S-expression) is a s-expression as well as a list. We know is a list because is enclosed by parenthesis.

There are some functions we can use in lists, the first introduced ones are car and cdr (pronounced could-er). car will return (I’m not even sure return is the correct term, but well) the first S-expression on a non-empty list, so it can return a list or an atom.

> (car (list 1 2 3))

< 1

> (car (list (list 1 2 3) 4 5 6))

< '(1 2 3)

In the first example 1 is the first element of the list and is an atom. In the second example the list is composed by a list and 3 other atoms, so the first element of the list is itself a list. The beauty of this, is that every expression is returning a value. Since the returned value of the second example is a list, and we know we can use car on lists, nothing prevents us of doing:

> (car (car (list (list 1 2 3) 4 5 6)))

< 1

The second function (called primitive in the book) is cdr. cdr also works on non-empty lists and it will return every element of the list after the first element, or in other words:

cdr = list - (car list)

Important to say is that the cdr of any list will always be a list. What happens with a one-element list?

(cdr (list 1))

You get returned (), an empty list, also referred to as null.

Other function introduced is cons, which takes two arguments: the first one is any S-expression, and the second is any list. The result is always a list. Since we know that cons only accepts a list as second argument, and that cdr only returns lists, we can already play with the concepts:

> (cons (car (list 4 3 2)) (cdr(list 1 6)))

< '(4 6)

So here we provided the first element of cons with the atom 4, and the second argument is the cdr of (1 6) that is 6. I did so to show that cdr always returns a list, so that 6 is not an atom, but a one element list (and therefore is able to be a valid argument for cons that requires a list as second argument).

I was also introduced to other ‘primitives’ such as null? (defined only for lists to check whether they are empty or not), atom? (takes any s-expression as argument and checks if the value is an atom), and eq?, that compares two non-numeric atoms.

Scheme has proved to be an interesting endeavour. I’m aware my close future will involve chaining expressions, probable frustration with recursion, and an industrial amount of parenthesis. This is a strange and unexplored land for me, a different way of looking at programming, just like Kanji is to roman alphabet. It is quite exciting.